By Hannah Summers

Chloe* says she will never

fully recover from the day her

daughter was taken from her following

a family court order.

“Someone slept in my house

because I couldn’t be left on my

own,” she recalls. “I lost nearly

two stone (28 pounds). I couldn’t

breathe, I couldn’t sleep. It was

horrific.” Hitting rock bottom,

Chloe made an attempt on her

own life.

Chloe says evidence that

she’d been a bad mother was

non-existent, and contact between

her daughter and her

daughter’s father had run

smoothly for years. But when

her child revealed she was

“scared of daddy” and refused

to spend time with him, Chloe’s

ex-partner took legal action.

Therapists were brought in

to assess the family; attempts to

force the girl to see her father,

a process Chloe describes as

“child abuse”, failed repeatedly.

Then the court ruled that all contact

between mother and child

should stop for at least 90 days.

“They said I’d ‘alienated’ her,”

Chloe explains.

The story may sound extreme,

but it is far from rare.

Tip of the iceberg

Official data is sparse about

the outcomes of private law children’s

cases – those where private

individuals try to resolve a

dispute in family court without

local authority involvement.

But there has been growing

alarm at the apparent increase in

the number of removals or custody

transfers against the wishes of

children, particularly where there

have been abuse allegations.

Dr Adrienne Barnett, a

non-practising barrister and reader

of law at Brunel University London,

explains: “Up until 2014 the

removals of children from their

primary carers did happen in private

law cases but were extremely

rare.

‘I’ve met women

who have been

beaten, raped and

imprisoned and

whose abusers

got access to their

children – sometimes

full custody’

“However, in

recent years the

small proportion

of published judgments

indicate an

increase – and we

know those are

just the tip of the

iceberg.”

Barnett is regularly contacted

by mothers who describe themselves

as victims of domestic

abuse and have had their children

removed due to allegations of “parental

alienation”.

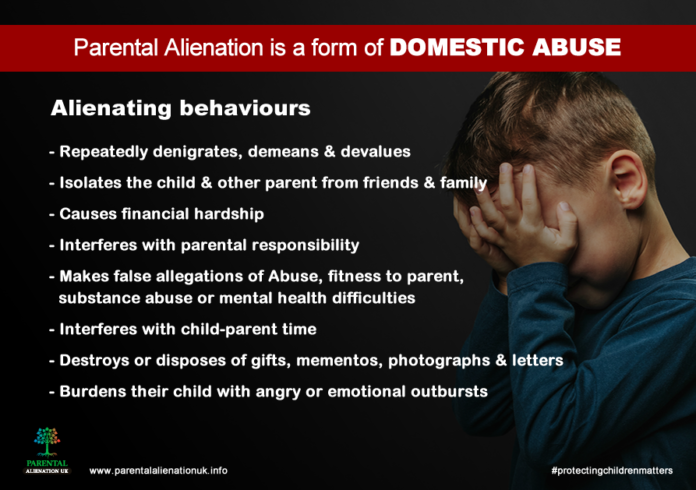

Belittling allegations

Parental alienation is commonly

described as a child’s unjustified hostility

or rejection of one parent for no

reason other than that they have been

manipulated – whether consciously

or not – by the other parent.

The concept stems from the

theory of parental alienation syndrome.

That was introduced by

the American psychiatrist Richard

Gardner and broadly interpreted

as a means of refuting mothers’

claims of child abuse. The notion

of a “syndrome” became widely

discredited but the concept of

parental alienation as a pattern of

behaviour has gained traction in

courtrooms worldwide.

In the last year, MPs, women’s

rights groups, academics and

organisations such as the United

Nations have raised alarm about

the use of parental alienation as a

litigation tool to counter claims of

domestic or sexual abuse.

Concerns have been raised

about professional acceptance of

the concept and the quality of experts

used by the courts in parental

alienation cases. There is also

a culture within the family court

system that seemingly results in

the minimisation of abuse allegations

by children and their parents.

Proponents of the theory believe

parental alienation is a widespread

form of child abuse and

have launched a petition in response

to a UN report calling for a

ban of its use amid claims of bias.

Drive for transparency

In the forthcoming weeks and

months, TBIJ will dig deeper into

the issue and examine how the

family courts are handling allegations

of abuse in private law cases.

Most of these hearings take

place behind closed doors. That

means public awareness of private

law proceedings is limited to the

small number of published judgments

– or what is documented by

journalists who have successfully

got the strict reporting restrictions

that apply to family cases lifted.

But, in May, private law cases

were brought under a family court

reporting pilot that has been running

in three key locations in England

and Wales since January in a

drive to improve transparency.

For the first time, journalists

are allowed to report what they observe

in these high conflict cases

about child contact as long as the

families remain

anonymous.

Crucially, parents

whose cases

fall under the pilot

can give interviews

to journalists.

That upends

the current

rules, which could

have meant those

talking about

their case publicly

could be found in

contempt of court.

TBIJ will use

the improved access

to family courts in Leeds,

Carlisle and Cardiff – as well as

analysing cases beyond the pilot –

to better understand how decisions

are being reached in some of the

most contentious cases brought

before judges.

Jess Phillips, shadow minister

for domestic violence, believes

increased scrutiny of the family

courts is vital to protect the safety

of children.

The Labor MP tells TBIJ: “The

situation is so poor at the moment

in the courts that we have completely

unregulated people giving

evidence on behalf of abusers and

the courts, and the government

feels completely comfortable

about it.

Phillips believes the public

needs to be more aware of how

parental alienation cases are playing

out in family courts. “I have

an inbox from around the country

with hundreds of cases and in my

own constituency, I am involved

in three live cases at present,” she

adds. “This is always the case –

it’s not a small issue.”

Three years ago the government

published a report that revealed

evidence of a “pro-contact

culture” within family courts. That

culture has arisen as the result of

a law that says having a relationship

with both parents is in the best

interests of children. The report,

however, found the courts place

undue priority on ensuring contact

with the non-resident parent. This

results in the systemic minimisation

and disbelief of allegations of

domestic abuse and child sexual

abuse.

‘I felt like I was powerless

and had no voice. One of the experts

knew I hadn’t done anything

wrong, but they were on the gravy

train’

In November 2020, the Ministry

of Justice launched a review

of the “presumption of parental

involvement”, but the findings are

yet to be published.

Those who advocate for survivors

of abuse say the govern-

‘I felt like I

was powerless

and had no

voice. One of

the experts

knew I hadn’t

done anything

wrong, but

they were

on the gravy

train’

ment’s progress has been disgracefully

slow.

Claire Waxman, London’s victims’

commissioner, says: “We

have a situation now which is so

embedded that anyone who alleges

domestic abuse or says their

children have disclosed abuse is

met with a counter allegation of

parental alienation.

“We knew about this worrying

issue three years ago, but we have

seen a shocking rise in the last two

years of victims contacting us to

share their awful experiences, and

we are frustrated the government

has sat on this and done nothing.”

The use of parental alienation

as a litigation tool has been repeatedly

raised in Parliament in recent

months, including during a debate

in March when Labor MPs called

for an urgent inquiry into the problem

of unregulated experts.

Phillips and the MP Alex Cunningham

reported that mothers

trying to protect their children

from abusive partners were being

accused of alienation by court-appointed

experts with few formal

qualifications and a vested financial

interest in finding “alienation.”

Meanwhile, the MP Taiwo

Owatemi, who had tabled the debate,

called for urgent reforms to

the Children and Family Court

Advisory and Support Service

(Cafcass), which was set up to be

the voice of the child in family

cases.

“Not only are utterly unqualified

individuals being allowed to

testify as supposed experts in these

cases, Cafcass too has overseen a

rise in such allegations,” Owatemi

said.

Forced therapy

In her case, Chloe was told she

would have to undergo expensive

therapy mandated by the court if

she was to have a chance of seeing

her daughter again.

“I had forced therapy as part of

the 90-day process where I was told

I had to change my ways,” she says.

“I felt like I was powerless and had

no voice. One of the experts knew

I hadn’t done anything wrong, but

they were on the gravy train.”

Eventually, she got her daughter

back but only after spending hundreds

of thousands of pounds on

therapy and legal bills. With every

penny of her savings drained, she

had to remortgage her home.

Not all mothers found to have

alienated their children can afford

the therapy. Some have been cut

off from their children for years as

a result.

Labour MP Anna McMorrin

said a “national scandal” was happening

in the family courts during

a House of Commons debate on the

victims and prisoners bill in June.

This part of the justice system continues

to “breed a culture that promotes

contact with those who have

been accused of abuse”, she said.

“Survivors of domestic or coercive

abuse are facing counter-allegations

of parental alienation as a

stock response to their own abuse

allegations. Courts have continued

to instruct unregulated experts

who are connected with the parental

alienation lobby and who are

known for dismissing domestic

abuse victims.”

Unsafe decisions are made as a

result, with sometimes catastroph

catastrophic

consequences for children, said

McMorrin who added that the situation

was now “critical”.

And in May, the Lib Dem MP

Sarah Olney told parliament: “The

continued reliance on self-declared

experts to provide evidence

in family courts is placing thousands

of children and vulnerable

women at risk, with allegations of

parental alienation closely linked

to cases of domestic abuse and coercive

control. I have heard first

hand from constituents just how

dangerous this can be.”

Olney highlighted the UN report

that condemned parental

alienation as a

“discredited and

unscientific pseudo-

concept” used

to undermine

mothers trying to

protect their children

from abuse.

The report recommended

that

states should legislate

to prohibit

the use of parental

alienation and

related experts in

courts.

Meanwhile, in

a landmark judgment

known as “Re C”, Sir Andrew

McFarlane, president of family

division in England and Wales,

said that while there was a “need

for rigor” when instructing psychologists

to give expert evidence,

tighter regulation was a matter for

parliament.

But MPs pushing for change

face a stalemate with the Ministry

of Justice, which insists it is up to

the judiciary to reject inappropriate

experts.

Jaime Craig, a consultant clinical

psychologist who has helped

produce guidance for the Family

Justice Council, says: “The ping

pong backwards and forwards –

whether the matter of regulation is

for the judiciary or the government

– leaves us in limbo with nobody

taking responsibility for protecting

the public.

“Both sides are passing the

buck and, meanwhile,

the courts

can and will still

choose to appoint

psychologists

without the necessary

qualifications.”

****

U K – b a s e d

Hannah Summers

reports on women’s

rights and the

law around the

world.

Some identifying

features have

been changed to

protect contributors to this piece.

If you have been affected by

the issues in this article and want

to share your experiences, please

contact bureaulocal@tbij.com

and put Family Court Files in the

subject line.